Four years after I took general relativity, my professor asked me to send him an old animation I had made during his course showing parallel transport of vectors around a line of latitude on the sphere. Actually, I wasn’t the one who had made it (though I was flattered that he had thought so!)

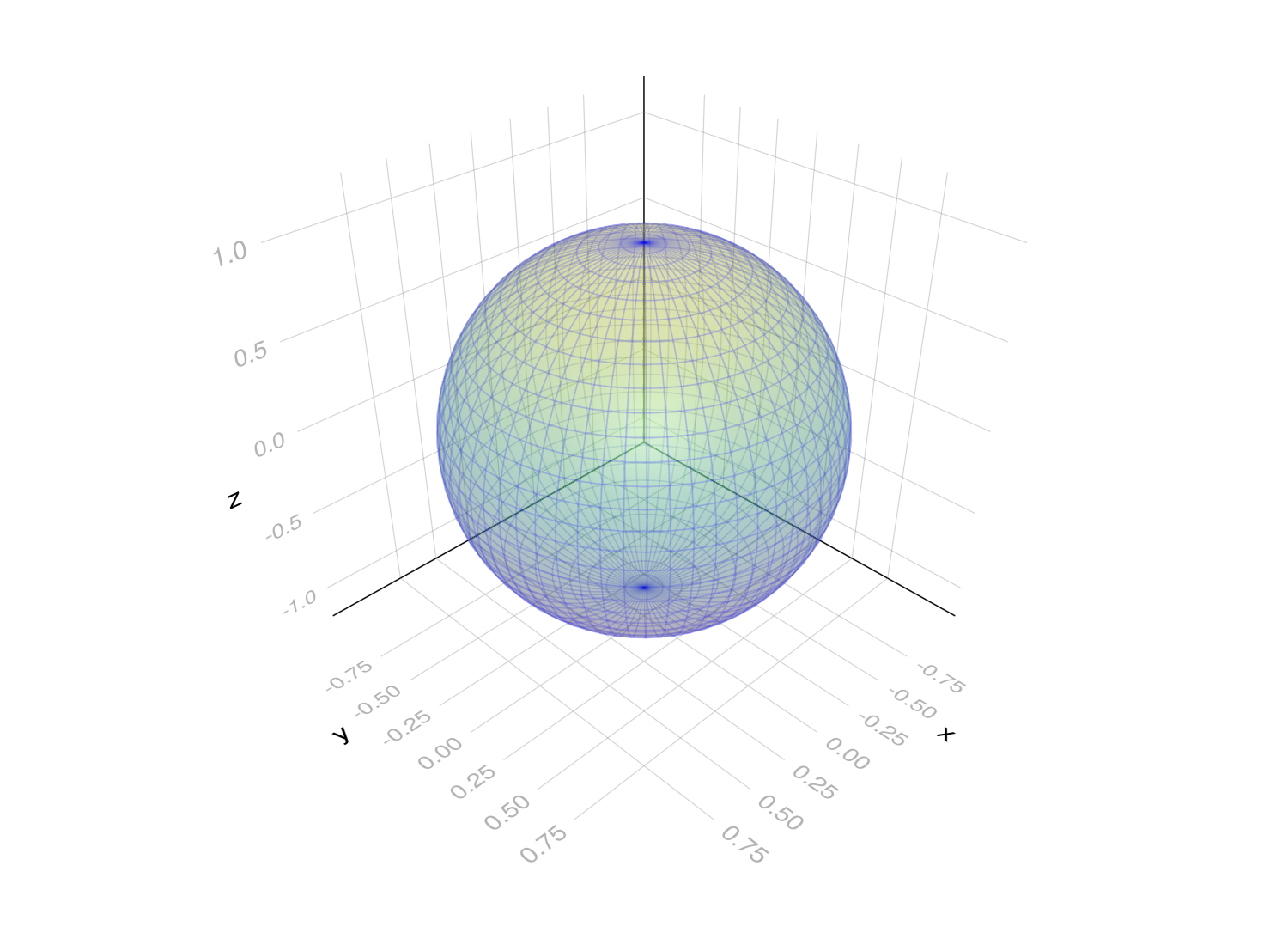

The tool I reached for was Julia. To my delight, the whole thing was rather simple to make. This was the humble result:

While taking that course, I remember thinking that numerically computing geodesics or simulating parallel transport were frightfully involved and required a mess of technical computing. Not so. If you have similar impression, read on.

This post describes how you might roll your own code for doing basic numerical general relativity (or rather, differential geometry) while only depending on external packages for dual numbers, differential equation solvers, and plotting.

Contents

- Step 0: Maps between manifolds

- Step 1: Automatic differentiation

- Step 2: Metrics and Christoffel symbols

- Step 3: Geodesics

- Step 4: Parallel transport

Step 0: Maps between manifolds

The very first task is to decide how to represent the relevant mathematical objects: manifolds, homomorphisms between them and tensor fields.

These things can seem complicated, but given a choice of coordinates, a point in a manifold is just a Vector of coordinates, a homomorphism is a function taking a Vector argument and returning a Vector, and tensor fields are the same thing, but returning a multidimensional Array.

For example, here’s an embedding \(f: 𝕊^2 → ℝ^3\) of a sphere into 3D space using the usual spherical coordinates \((θ, φ)\), as a Julia function:

f((θ, φ)) = [

sin(θ)cos(φ)

sin(θ)sin(φ)

cos(θ)

]

Notice this has one vector argument which is de-structured into two scalars.

julia> f([π/2, 0]) # meridian point on the equator

3-element Vector{Float64}:

1.0

0.0

6.123233995736766e-17

Here’s how you might use this embedding to plot a surface with Makie.jl:

using GLMakie

points = [f([θ, φ]) for θ ∈ range(0, π, 32), φ ∈ range(0, 2π, 64)]

x, y, z = eachslice(stack(points), dims=1)

wireframe(x, y, z, transparency=true, alpha=0.1, color=:blue)

surface!(x, y, z, transparency=true, alpha=0.2)

You could imagine doing something more involved like defining an object-oriented zoo of types for manifolds, coordinate charts, transition functions, homomorphisms, tensor fields, and so on. Don’t bother. Dead simple is good.

Step 1: Automatic differentiation

Differential geometry has lots of “\(∂\)”s.

We want to have derivatives of homomorphisms such as f be computed automatically.

There are many approaches to doing this with Julia, ranging from symbolic differentiation with Symbolics.jl to using Zygote.jl to differentiate code.

In our case, we’re not doing anything fancy — just building vectors with mathematical functions line sin — so all we’ll need is an implementation of dual numbers.

Dual numbers

If you extend the reals by adding an element \(ε ≠ 0\) satisfying \(ε^2 = 0\), then you can get derivative information for free when you evaluate a function with \(+ε\), since

\[f(x + ε) = f(x) + ε f'(x)\]by Taylor’s theorem. The function value is the real part, and its derivative is the coefficient of \(ε\). If we denote this coefficient by \(⟨\quad⟩_ε\), we have our dual number derivative formula:

\[f'(x) = ⟨f(x + ε)⟩_ε\]To do this in Julia, the TaylorSeries.jl package is sufficient.

Here’s computing the derivative of \(\sin(x)\) at \(x = \frac{π}{3}\):

julia> using TaylorSeries

julia> sin(Taylor1([π/3, 1]))

0.8660254037844386 + 0.5000000000000001 t + 𝒪(t²)

julia> ans.coeffs[2] # get the ε term

0.5000000000000001

julia> ans == cos(π/3)

true

To make accessing the \(ε\) coefficient clearer, we may define

epsilonpart(a::Taylor1{T}) where T = get(a.coeffs, 2, zero(T))

which works even if, for some reason, a is truncated to \(𝒪(1)\) so that a.coeffs has no second component.

We can pack this into a function to take the derivative of functions on \(ℝ\).

∂(f, x::Number) = epsilonpart.(f(Taylor1([x, 1])))

which would be used like so:

julia> ∂(sin, 1) ≈ cos(1)

true

Computing Jacobians

This trick works for functions of vectors, too. We just add \(+ε\) to the component we want to differentiate with respect to:

\[∂_μ f(\vec x) = \bigg⟨ f\left(\begin{bmatrix}x^1 \\ \vdots \\ x^μ + ε \\ \vdots \\ x^n \end{bmatrix}\right) \bigg⟩_ε\]For a vector-valued function \(f : ℝ^m → ℝ^n\), we have a matrix of derivatives (a Jacobian).

\[∂f(\vec x) ≔ \mqty[ ∂_μ f^ν(\vec x) ]_{μν} = \mqty[ ∂_1 f(\vec x) \\ \vdots \\ ∂_m f(\vec x) ] = \mqty[ ∂_1 f^1(\vec x) & \cdots & ∂_1 f^n(\vec x) \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ ∂_m f^1(\vec x) & \cdots & ∂_n f^n(\vec x) ]\]Note. The Jacobian is conventionally the transpose of this, but we would like to have the first dimension (along columns) to run along the first index that appears, \(μ\), and the second dimension (along rows) along the the second index, \(ν\). This means indices in code will appear in the same order as in the maths, making the generalisation to higher order tensors easier.

Spelling this out with our dual number derivative formula:

\[∂f(\vec x) = \mqty[ \bigg⟨f^1\qty(\mqty[x^1 + ε\\\vdots\\x^n])\bigg⟩_ε & \cdots & \bigg⟨f^m\qty(\mqty[x^1 + ε\\\vdots\\x^n])\bigg⟩_ε \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \bigg⟨f^1\qty(\mqty[x^1\\\vdots\\x^n + ε])\bigg⟩_ε & \cdots & \bigg⟨f^m\qty(\mqty[x^1\\\vdots\\x^n + ε])\bigg⟩_ε \\ ]\]Here’s a literal Julia implementation:

function ∂(f, x::AbstractArray)

I = eachindex(x)

derivs = [epsilonpart.(f([Taylor1([x[i], i == j]) for i ∈ I])) for j ∈ I]

stack(derivs, dims=1) # stack vectors as rows in a matrix

end

Let’s test it on our sphere embedding map f.

julia> ∂(f, [π/2, 0])

2×3 Matrix{Float64}:

6.12323e-17 0.0 -1.0

0.0 1.0 -0.0

The quantity \(∂_μ f^ν (x)\) is then given by ∂(f, x)[μ,∨].

We can check it is correct by comparing it to the analytic Jacobian:

julia> ∂f((θ, φ)) = [

+cos(θ)cos(φ) +cos(θ)sin(φ) -sin(θ)

-sin(θ)sin(φ) +sin(θ)cos(φ) 0

];

julia> all(∂(f, x) ≈ ∂f(x) for x in eachcol(rand(2,100)))

true

So far so good.

Higher order derivatives

But what about second order derivatives?

Luckily, since this is Julia, TaylorSeries.jl is generic and lets you construct Taylor series whose coefficients are themselves Taylor series.

This means our implementation for ∂ works even on functions which call ∂, letting us compute higher order derivatives in the obvious way.

For example, \(∂_μ ∂_ν f^λ(\vec x)\) may be evaluated as:

∂∂f(x) = ∂(x′ -> ∂(f, x′), x)

Notice that this produces a three dimensional array, since \(∂_μ ∂_ν f^λ(\vec x)\) has three indices.

julia> ∂∂f([1,2])

2×2×3 Array{Float64, 3}:

[:, :, 1] =

0.350175 -0.491295

-0.491295 0.350175

[:, :, 2] =

-0.765147 -0.224845

-0.224845 -0.765147

[:, :, 3] =

-0.540302 -0.0

-0.0 -0.0

This shows how ∂ diverges slightly from other Jacobian implementations: ours doesn’t flatten extra dimensions in order to produce a matrix.

Step 2: Metrics and Christoffel symbols

To do things like compute geodesics and simulate parallel transport, we need the metric \(g_{μν}\) and Christoffel symbols \(Γ^λ{}_{μν}\) for our manifold.

Induced metrics for embedded manifolds

If our manifold happens to be a parametric surface embedded in \(ℝ^n\), such as our sphere embedding \(f : 𝕊^2 → ℝ^3\), then we should be able to compute the metric on the surface induced by the ambient Euclidean metric, \(η = \operatorname{diag}(1, \dots, 1)\). Specifically, the induced metric \(g\) is the pullback of \(η\) by \(f\),

\[g ≔ f^*η .\]The pullback \(f^*\) is defined so that the above is equivalent to

\[g(\vec u, \vec v) ≔ η(f_*\vec u, f_*\vec v)\]for any input vectors, where \(f_*\) is the pushforward — nothing but the Jacobian matrix from before.

\[f_* \big|_{\vec x} ≡ ∂f(\vec x)\]With coordinates, the action on a vector may be written as

\[(f_* \vec u )^ν\big|_{\vec x} = ∂_μ f^ν(\vec x) \, u^μ\]so that the component form of \(g(\vec u, \vec v)\) is:

\[\begin{align*} g_{μν} u^μ v^ν &= η_{ρσ} \, ∂_μ f^ρ u^μ \, ∂_ν f^σ u^ρ \\ g_{μν} &= ∂_ρ f^μ \, η_{μν} \, ∂_σ f^ν \\ \end{align*}\]Really, this is just matrix-matrix multiplication.

\[g = f_* η (f_*)^\intercal = f_* (f_*)^\intercal\]The Julia translation is just as pretty:

g(x) = let ∂f = ∂(f, x)

∂f*∂f'

end

This should give us the metric on the sphere. Let’s sanity check it again:

julia> g_sphere((θ, ϕ)) = [

1 0

0 sin(θ)^2

];

julia> all(g(x) ≈ g_sphere(x) for x in eachcol(rand(2, 100)))

true

Christoffel symbols

Now comes the interesting maths. The Christoffel symbols are defined in terms of the metric and its first derivatives as

\[Γ^λ{}_{μν} = \frac12g^{λσ}\qty(\partial_μ g_{σν} + \partial_ν g_{σμ} - \partial_σ g_{μν}) .\]Implementing this in Julia is just a matter of summing over all the right components.

We could do this with sum(... for μ ∈ 1:n), but a nice way of doing this is to use a package like TensorOperations.jl which provides a macro enabling Einstein summation notation.

using TensorOperations

function Γ(g, x)

∂g = ∂(g, x) # 3-index array

@tensor Γ[λ,μ,ν] := 2\inv(g(x))[λ,σ]*(∂g[μ,σ,ν] + ∂g[ν,σ,μ] - ∂g[σ,μ,ν])

end

Within the @tensor expression, any Julia identifier inside [ ] is treated as an index, whose range is automatically computed at runtime, with repeated indices summed.

The := means a new array is created, whereas = would write into an existing array.

To test this out and check that the basic symmetry \(Γ^λ{}_{μν} = Γ^λ{}_{νμ}\) holds:

julia> Γ(g, [1,2])

2×2×2 Array{Float64, 3}:

[:, :, 1] =

0.0 0.0

0.0 0.642093

[:, :, 2] =

0.0 -0.454649

0.642093 0.0

julia> ans == permutedims(ans, (1, 3, 2))

true

Step 3: Geodesics

Now we get to the cool stuff — geodesics.

A geodesic is a curve \(\vec x(t)\) which satisfies the geodesic equation,

\[\dot x^μ(t) ∇_μ \dot x^λ(t) = 0 .\]In words, the velocity vector \(\dot x\) is covariantly constant along the direction it points. Unpacking the covariant derivative, this becomes:

\[\dot x^μ(t) ∂_μ \dot x^λ(t) + \dot x^μ(t) Γ^λ{}_{μν} \big|_{\vec x(t)} \dot x^ν(t) = 0\]Simplifying using the chain rule \(\frac{\dd x^μ}{\dd t}\frac{∂\dot{x}^λ}{∂x^μ} = \ddot x^λ\) and leaving the position and \(t\)-dependence implicit, we have a system of second order ordinary differential equations

\[\ddot x^λ = -Γ^λ{}_{μν} \dot x^μ \dot x^ν .\]Julia has good support for numerically solving ODEs.

We will use the DifferentialEquations.jl package.

It requires the ODE to be put into standard form,

\(\ddot{x} = f_\text{geodesic}(\dot{x}, x, g, t)

.\)

The third argument \(g\) can contain any extra data needed to evaluate \(\ddot{x}\), which is just the metric in our case.

Additionally, the first argument of the Julia function is the array ẍ to write the derivatives into (optional, but leads to better performance).

function geodesic!(ẍ, ẋ, x, g, t)

@tensor ẍ[λ] = -Γ(g, x)[λ,μ,ν]*ẋ[μ]*ẋ[ν]

end

Solving ODEs in Julia.

Here’s an example of numerically solving the geodesic equation with some initial data. Take our sphere, and imagine launching a particle eastward along the equator, \(θ = π/2\).

julia> using DifferentialEquations

julia> ẋ0 = [0., 1.]; x0 = [π/2, 0.]; tspan = (0, 10);

julia> prob = SecondOrderODEProblem(geodesic!, ẋ0, x0, tspan, g)

ODEProblem with uType ArrayPartition{Float64, Tuple{Vector{Float64}, Vector{Float64}}} and tType Int64. In-place: true

timespan: (0, 10)

u0: ([0.0, 1.0], [1.5707963267948966, 0.0])

julia> sol = solve(prob);

The solution object sol is matrix-like, with four rows and \(n\) columns

so we can extract just \(\vec x(t)\) by taking the bottom two rows.

julia> sol[3:4,:]

2×6 Matrix{Float64}:

1.5708 1.5708 1.5708 1.5708 1.5708 1.5708

0.0 0.00141306 0.0155436 0.156849 1.56991 10.0

We can see that our geodesic curve stays at the equator \(θ = π/2\) and orbits around with \(φ\) increasing at one radian per unit time.

Boring, but correct!

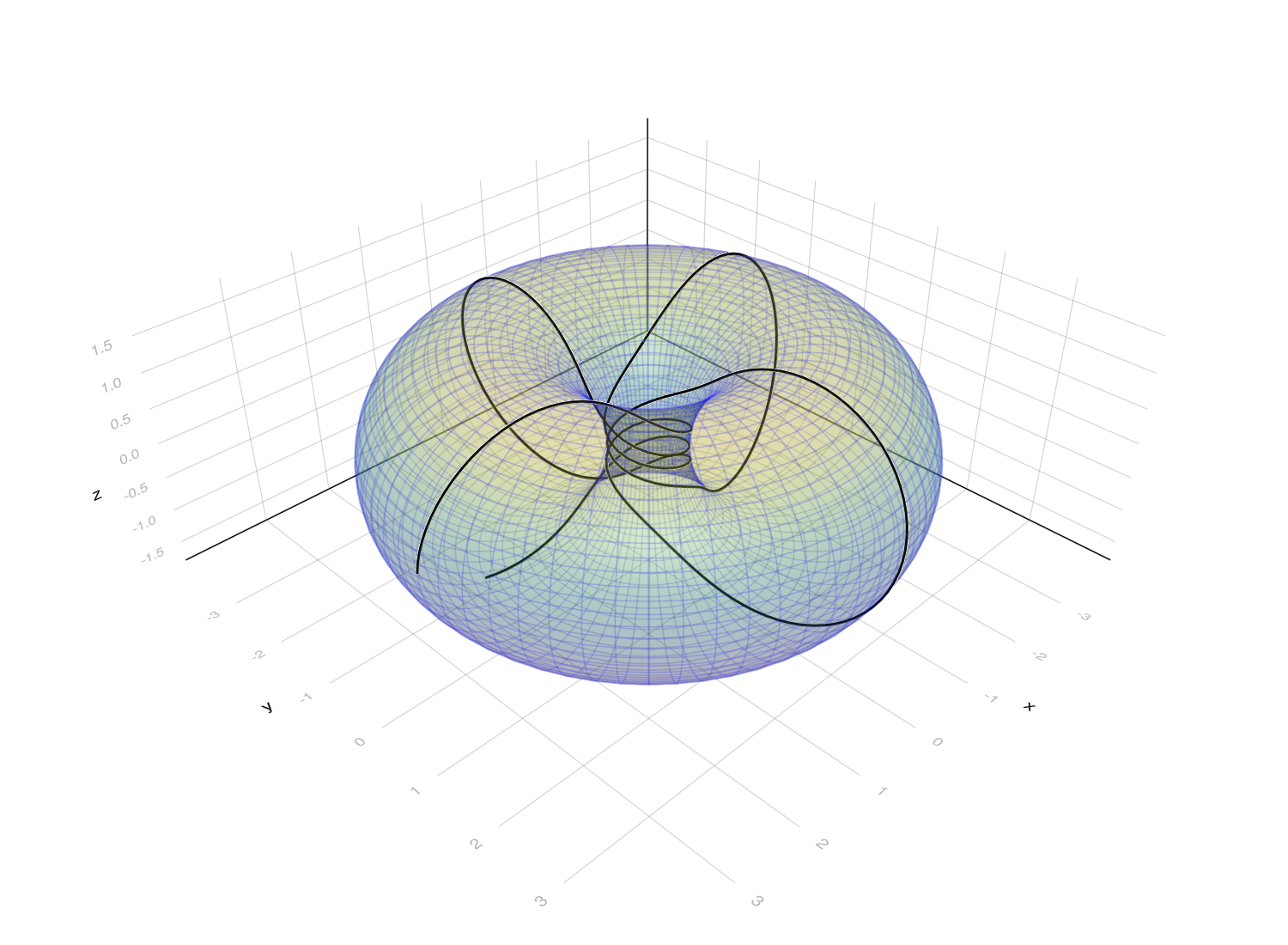

Interesting example: Doughnut geodesics

Let’s combine what we have so far to compute some geodesic curves on a torus.

The code is presented as a script for readability, but if you wanted to use it, you should pack everything into functions to avoid global variables and use something like Revise.jl.

using TaylorSeries

using TensorOperations

using DifferentialEquations

using GLMakie

epsilonpart(a::Taylor1{T}) where T = get(a.coeffs, 2, zero(T))

function ∂(f, x)

I = eachindex(x)

derivs = [epsilonpart.(f([Taylor1([x[i], i == j]) for i ∈ I])) for j ∈ I]

stack(derivs, dims=1) # stack vectors as rows in a matrix

end

function Γ(g, x)

∂G = ∂(g, x)

@tensor Γ[λ,μ,ν] := 2\inv(g(x))[λ,σ]*(∂G[μ,σ,ν] + ∂G[ν,σ,μ] - ∂G[σ,μ,ν])

end

function geodesic!(ẍ, ẋ, x, g, t)

@tensor ẍ[λ] = -Γ(g, x)[λ,μ,ν]*ẋ[μ]*ẋ[ν]

end

R = 2

r = 1.5

# parametric torus

f((θ, φ)) = [

(R + r*cos(φ))*cos(θ),

(R + r*cos(φ))*sin(θ),

r*sin(φ),

]

# embedded torus metric

g(x) = let df = ∂(f, x)

df*df'

end

# plot torus

circle = range(0, 2π, length=64 + 1)

x, y, z = eachslice(stack([f([θ, φ]) for θ ∈ circle, φ ∈ circle]), dims=1)

wireframe(x, y, z, transparency=true, alpha=0.1, color=:blue)

surface!(x, y, z, transparency=true, alpha=0.2)

# compute geodesic

prob = SecondOrderODEProblem(geodesic!, [0.06, 1], [0., 0.], (0, 20), g)

sol = solve(prob)

# plot geodesic

path = mapslices(f, sol(0:0.1:30)[3:4,:], dims=1)

lines!(path, linewidth=3, color=:black)

Step 4: Parallel transport

The other cool thing you can do once you have a metric is slide things along a path \(γ(t)\) irrotationally.

If \(\vec U(t)\) is a vector defined everywhere on the path \(γ(t)\), then it is the parallel transport of some initial vector \(U(0)\) if it satisfies the parallel transport equation,

\[\dot γ^μ(t) ∇_μ U^λ(t) = 0 .\]Like for the geodesic equation, unpacking the covariant derivative leads to the system of differential equations

\[\dot γ^μ(t) ∂_μ U^λ(t) + \dot γ^μ(t) Γ^λ{}_{μν}\big|_{γ(t)} U^ν(t) = 0\]which, more succinctly, is

\[\dot U^λ = -Γ^λ{}_{μν} \dot γ^μ U^ν .\]This is only a first order differential equation, but now we have two pieces of data to provide as parameters: the metric \(g\) and the path, \(γ\).

In Julia, the differential equation function looks like

function paralleltrans!(u̇, u, (g, γ), t)

γ̇ = ∂(γ, t)

@tensor u̇[λ] = -Γ(g, γ(t))[λ,μ,ν]*γ̇[μ]*u[ν]

end

and solving it, for the sphere example, looks like:

julia> f((θ, φ)) = [sin(θ)cos(φ), sin(θ)sin(φ), cos(θ)];

julia> g(x) = let ∂f = ∂(f, x)

∂f*∂f'

end;

julia> γ(t) = [π/4, t]; # circle of latitude

julia> U0 = [0., 1.]; # initial vector pointing east

julia> prob = ODEProblem(paralleltrans!, U0, 10, (g, γ))

ODEProblem with uType Vector{Float64} and tType Int64. In-place: true

timespan: (0, 10)

u0: 2-element Vector{Float64}:

0.0

1.0

julia> sol = solve(prob);

The resulting solution object sol is matrix-like, as before. But we can also call it like sol(t) to get the interpolated approximation for a given time.

This means we can animate it, with a little extra setup code: